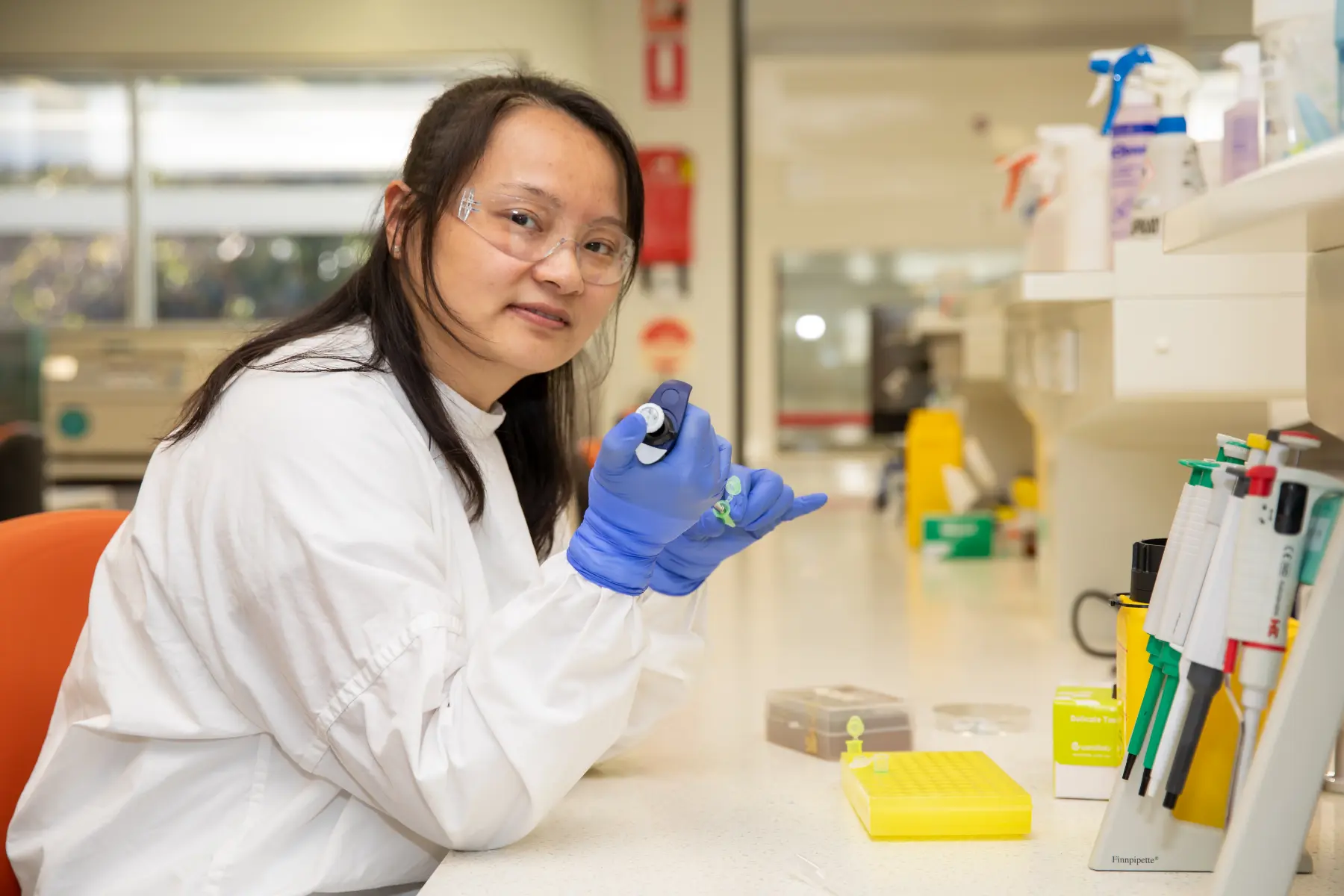

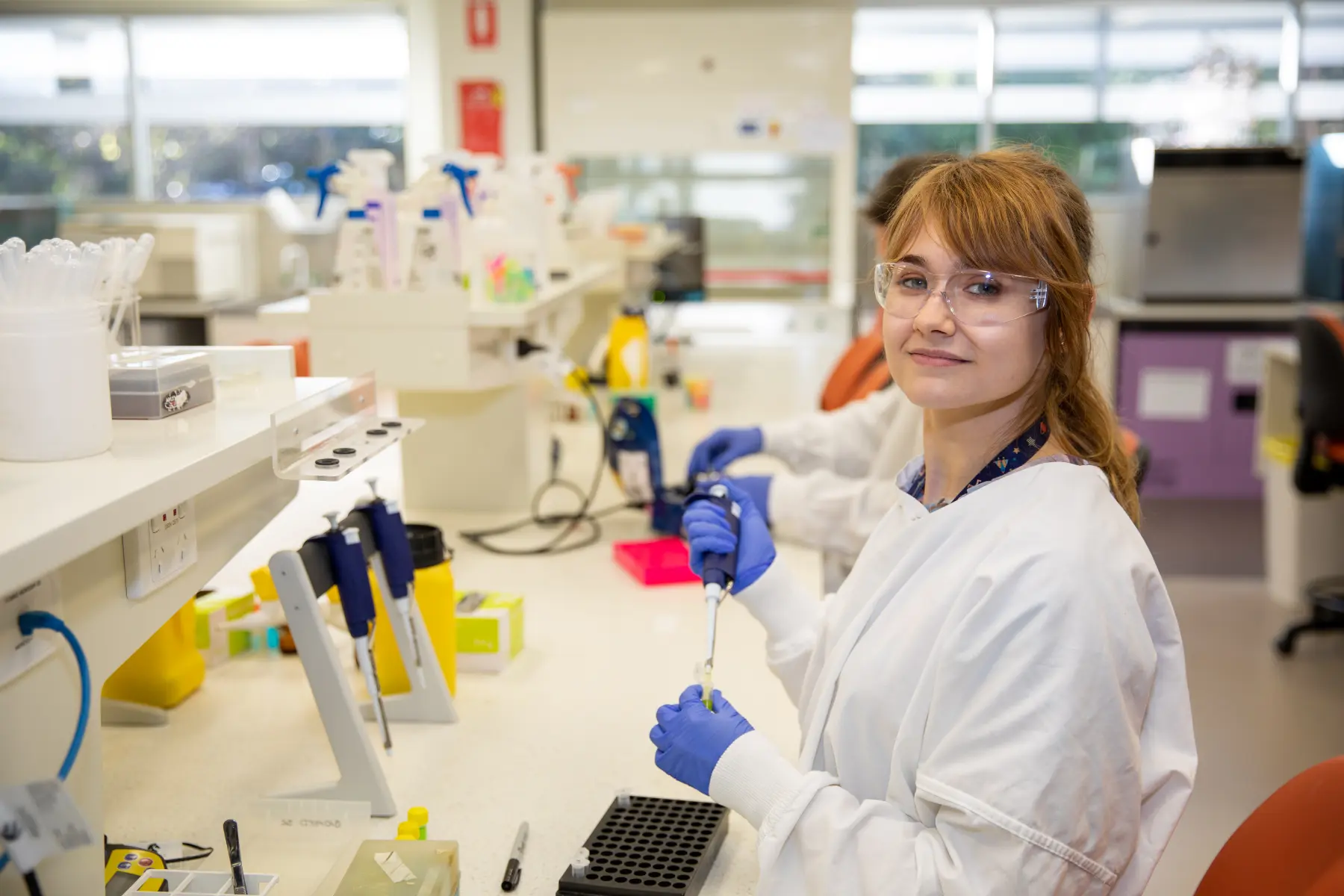

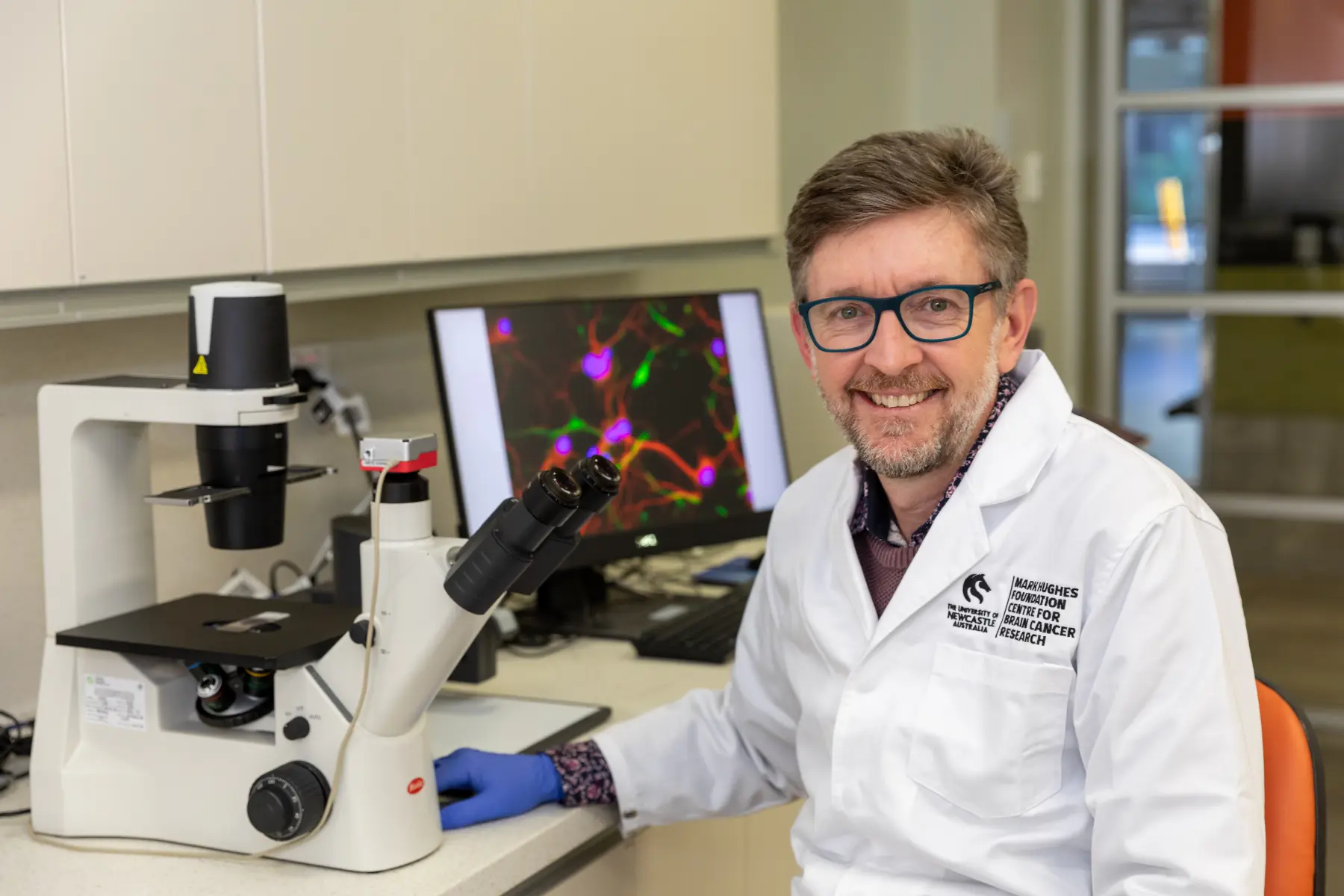

We would like to congratulate Biobanking and Clinical Research Manager, Cassandra Griffin (pictured), Professor Christine Paul and Dr James Lynam on the publication of their paper in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

The piece is written from the perspective of Cassandra Griffin, who was present during the events that are described. The other two authors are senior leaders associated with the brain donation program who were closely involved in the preparation of the manuscript.

Full Paper – Canadian Medical Association Journal

As I sat in the hospice room, with the lights dimmed and a sunset glow outside, the young woman before me signed a consent form to donate her brain. A haunting moment that, as a clinical researcher, I sought to understand and commemorate.

Sarah was a force to be reckoned with. Strong, golden-haired, brimming with life and a fierce love for her friends and family. A talented dancer, teacher, and nurturer who spent every spare moment honing her craft and pushing herself to the limit. Her pointe shoes, worn down to threads, reflected her dedicated hours.

As I sat and spoke with Sarah’s father, a man with kind eyes and a warm smile, he told me that Sarah grew up discussing organ donation around the family dinner table, learning the value of helping someone else. With pride, he told me stories of Sarah looking beyond herself and providing others a chance to shine, nurturing creativity, confidence, and joy through dance.

He spoke of her resolute strength, persevering through surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and alternative approaches to care. He smiled as he told of her unwillingness to succumb, absurdly finding herself onstage at a rock concert, pirouetting in a beanie from a brain cancer charity just 24 hours after an aggressive cycle of chemotherapy.

Glioblastoma does not discriminate and after years of fighting her insidious disease, the reality was that Sarah’s tumour had progressed and ceased responding to treatment. Brain cancer is said to take a person before it takes a life. With no further source of clinical hope, little seemed to be left for Sarah or her family to do. Sarah could no longer dance and was unsteady on her feet, but she held fiercely to her desire to help others and had made plans for a legacy beyond monetary value, one that she assured her family would provide hope for the future. She intended to donate her brain.

Donation would be a rare opportunity to regain control and to make a deeply personal choice to establish a legacy and give meaning to the family’s suffering. Their wish was that one day there would be another little girl who would don pink ballet shoes and dance in a world free from glioblastoma.

However, repeated assessments from Sarah’s care team determined that Sarah’s condition had deteriorated to the extent that she was no longer deemed capable of giving consent, meaning Sarah’s donation would not occur. Her family was devastated. Following an ethical appeal, a waiver of consent for donation to the Mark Hughes Foundation Biobank, to be signed by her family, was granted.

It was clear beyond any doubt how important this legacy would be to both Sarah and her loved ones. As her sister returned to her bedside vigil, she quietly whispered in Sarah’s ear that Sarah would have her wish.

When I arrived at the hospice to obtain the requisite signatures from her family, I found Sarah’s sister and father in tears. A chill ran through me. Was I too late? But then I realized that they were smiling through the tears.

“She’s awake”, they said. “She’s talking!”

The room was dark to avoid any strain on her eyes and the setting sun danced a gentle glow across the bed. I saw a girl my age, with golden hair and a petite form surrounded by photos of her 3 “children” — a dog, a cat, and a cockatoo. Memories of a short life lived with passion, adventure, and love. We spoke briefly, her speech laboured but every word chosen with intent. “I want you to take my brain so that nobody else goes through this.”

Her father moved to her side, his movements gentle yet deliberate. In hushed tones and with a smile, he reached behind her. “Let’s sit you up, squirt.” He raised the head of the bed and placed the pen in her hand. Just 24 hours previously, we had believed Sarah was no longer capable of higher-order brain function. Her fine motor skills had failed long before this and she had not been able to hold a pen anymore — but somehow, in this moment, she could.

She signed her name clearly. It was just a signature, but to Sarah and to all of us who were present, it was a miraculous show of willpower and altruism.

Sarah laid down to sleep shortly after and did not wake again. A few short days later, with her family at her side, immersed in memories of a life cut far too short, she died peacefully.

Sarah’s story isn’t unique. Many who care for people on the cusp of death will have stories or anecdotes of such “Lazarus” events, of people miraculously improving for a short time, of previously unresponsive patients smiling at an innocuous joke or shedding a single tear in a final goodbye. In Sarah’s case, this moment was a reaffirming example of the psychological value of brain donation. To witness an individual defy the boundaries of physiological understanding and regain higher cognitive function in a terminal state was a humbling and awe-inspiring demonstration of the strength of the human spirit.

This inspiring young woman and her devoted family left an indelible mark; a selfless donation that enshrined a legacy of hope.